![]() Reiwa – Heisei – Showa – Taisho – Meiji

Reiwa – Heisei – Showa – Taisho – Meiji

The Meiji period (明治時代 Meiji-jidai), also known as the Meiji era, is a Japanese era which extended from September 1868 through July 1912. This period represents the first half of the Empire of Japan. During this time society moved from being an isolated feudalism system to its modern form. Fundamental changes affected its social structure, internal politics, economy, military, and foreign relations.

Meiji restoration and the emperor

Main article: Abolition of the han system

On February 3rd, 1867, fifteen-year-old prince Mutsuhito succeeded his father, Emperor Kōmei, to the Chrysanthemum Throne as the 122nd emperor.

Imperial restoration occurred the next year, on January 3rd, 1868, with the formation of the new government. The Tokugawa Shogunate was overthrown with the fall of Edo in the summer of 1868, and a new era called Meiji, meaning “enlightened rule”, proclaimed.

The first reform was the promulgation of the Five Charter Oath in 1868, a general statement of the aims of the Meiji leaders to boost morale and win financial support for the new government. Its five provisions consisted of

- Establishment of deliberative assemblies

- Involvement of all classes in carrying out state affairs

- The revocation of sumptuary laws and class restrictions on employment

- Replacement of “evil customs” with the “just laws of nature” and

- An international search for knowledge to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.

Implicit in the Charter Oath was an end to exclusive political rule by the bakufu and a move toward more democratic participation in government. To implement the Charter Oath, a constitution with eleven articles was drawn up. Besides providing for a new Council of State, legislative bodies, and systems of ranks for nobles and officials, it limited office tenure to four years. This allowed public balloting, provided for a new taxation system, and ordered new local administrative rules.

The Meiji Government

The Meiji government assured the foreign powers that it would follow the old treaties negotiated by the bakufu. It announced that it would act in accordance with international law. Mutsuhito, who was to reign until 1912, selected a new reign title—Meiji, or Enlightened Rule. This was to mark the beginning of a new era in Japanese history. To further dramatize the new order, the capital was relocated from Kyoto, where it had been situated since 794. It was relocated to Tokyo (Eastern Capital), the new name for Edo. In a move critical for the consolidation of the new regime, most daimyo voluntarily surrendered their land and census records to the emperor in the abolition of the Han system, symbolizing that the land and people were under the emperor’s jurisdiction.

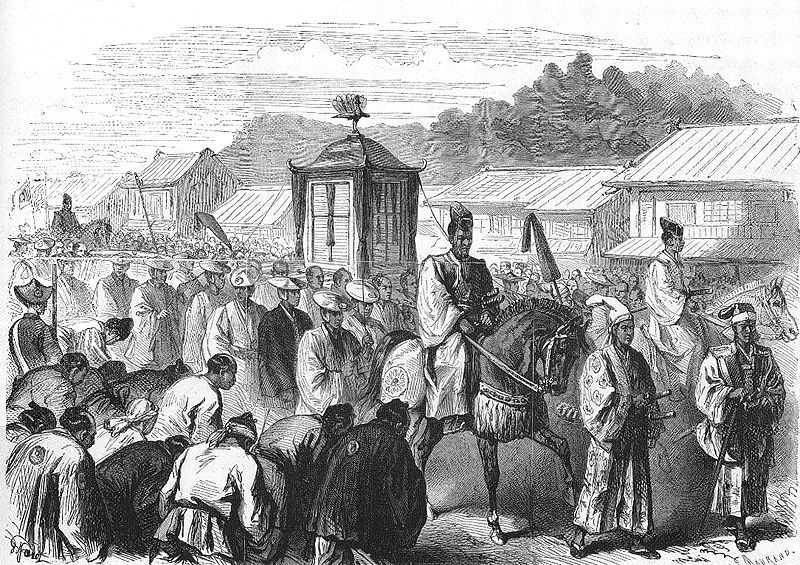

The Meiji Restoration and the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867: The fifteen-year-old Meiji Emperor, moving from Kyoto to Tokyo, at the end of 1868, after the fall of Edo.

Confirmed in their hereditary positions, the daimyo became governors, and the central government assumed their administrative expenses and paid samurai stipends. In 1871, prefectures replaced the han, and authority continued to flow to the national government. Officials from the favored former han, such as Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Hizen staffed the new ministries. Formerly out-of-favor court nobles and lower-ranking, but more radical, samurai replaced bakufu (tent government) appointees, daimyo, and old court nobles as a new ruling class appeared.

What is a daimyo/shogun?

At the top of Japanese feudal society was the shogun. The shogun were the vassal lords, known as daimyo [DIME-yo]. The daimyo were large landholders who held their estates at the pleasure of the shogun. They controlled the armies that were to provide military service to the shogun when required.

Emperor Meiji in his fifties

(Syncretism is a union or attempted fusion of different religions, cultures, or philosophies — like Halloween, which has both Christian and pagan roots, or the combination of Aristotelian philosophy with the belief system of the early punk rock practitioners. )

Inasmuch as the Meiji Restoration had sought to return the emperor to a preeminent position, efforts were made to establish a Shinto-oriented state, like 1,000 years earlier. Since Shinto and Buddhism had molded into a syncretic belief in the prior 1,000 years, a new State Shinto had to be constructed for that purpose. The Office of Shinto Worship was established, ranking even above the Council of State in importance. The kokutai ideas of the Mito school were embraced, and the divine ancestry of the imperial house was emphasized. The government supported Shinto teachers, a small but important move. Although the Office of Shinto Worship was demoted in 1872, by 1877 the Home Ministry controlled all Shinto shrines. Certain Shinto sects were also given state recognition. Shinto was released from Buddhist administration and its properties restored. Although Buddhism suffered from state sponsorship of Shinto, it had its own resurgence. Christianity also was legalized, and Confucianism remained an important ethical doctrine. Increasingly, however, thinkers identified more and more with Western ideology and methods.

Comments